The concubine and the hot cup of tea

There are many stories and legends surrounding the invention, or rather the discovery, of silk.

There are many stories and legends surrounding the invention, or rather the discovery, of silk.

One interesting – and entirely conceivable – myth is that Lei Zu, the concubine of the “Yellow Emperor” Huang-Di, went to sit in the shade of a mulberry tree to drink a cup of tea in around 2560 BC when suddenly a silkworm cocoon fell into the hot liquid. Within minutes an infinitely long silk thread emerged from this cocoon.

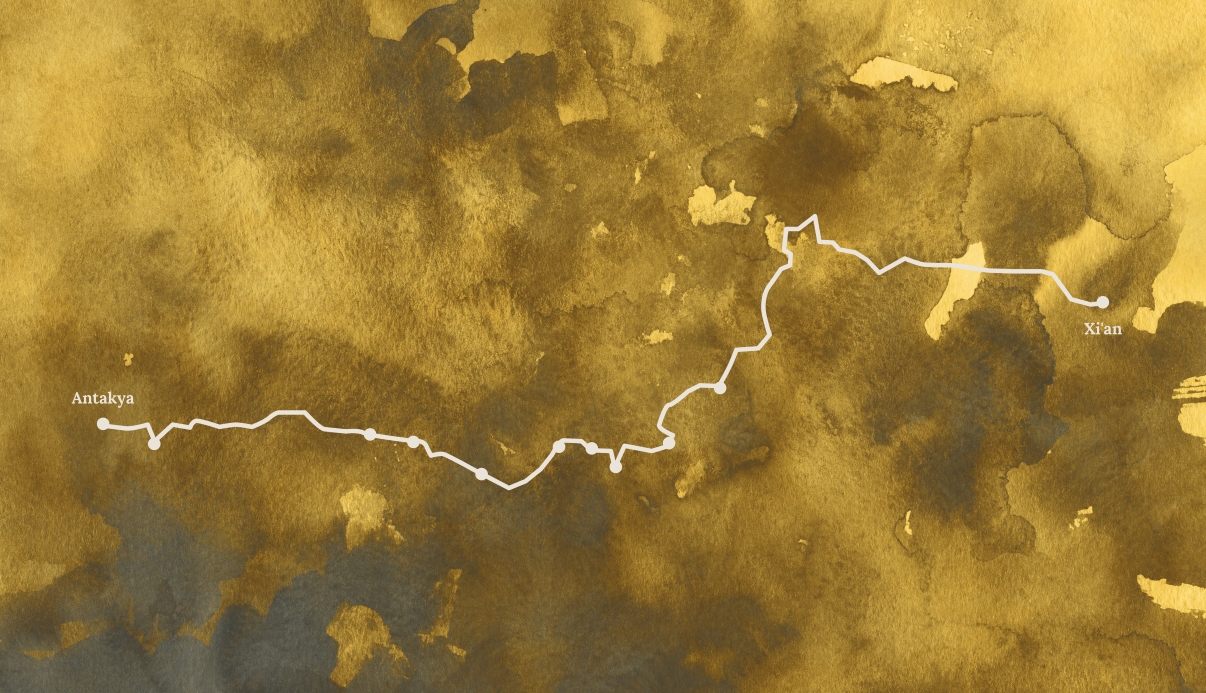

This could well have been the hour of birth of silk spinning. In any case, it prompted the Emperor to breed silkworms from then on. The production of silk was the best-kept secret of the Chinese Empire. Anyone guilty of betraying the secret would face the death penalty.

And so it was possible to hide this secret from the rest of the world for 3000 years. Until two monks set out from Constantinople in 550 AD …

Two Monks – One Secret

The Roman-Persian Wars denied the Emperor Justinian the noble silk fabric, which was popular at his court and was often worn there. The Emperor was on the verge of sending out ships through the Arabian Gulf when he heard of two monks who had returned from their pilgrimage through China and the Orient and had smuggled out some silkworm cocoons.

Only then was it discovered that the silk did not grow on bushes like cotton but was spun from a cocoon by a caterpillar fed on mulberry leaves.

Immediately the monks were ordered to undertake a second journey to bring the eggs of these useful insects back to Constantinople where mulberry trees were in plentiful supply. This happened in the year 565 AD.

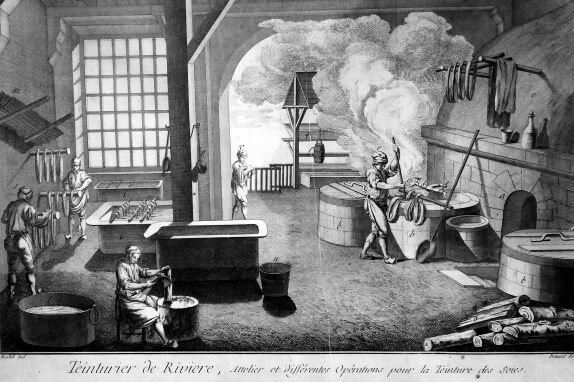

They hid a small quantity of eggs in their hollow walking sticks and took them to Greece where they hatched in the following spring. The silkworms multiplied rapidly and soon there were silk factories in Constantinople, Athens, Corinth and Thebes. Silk production originated here and branched out, starting in Italy and then spreading to Spain and France.

Frederick the Great also wanted to establish silk cultivation in Germany. It was an undertaking doomed to failure because the climate was unsuitable and the intensive cultivation methods were unpopular.